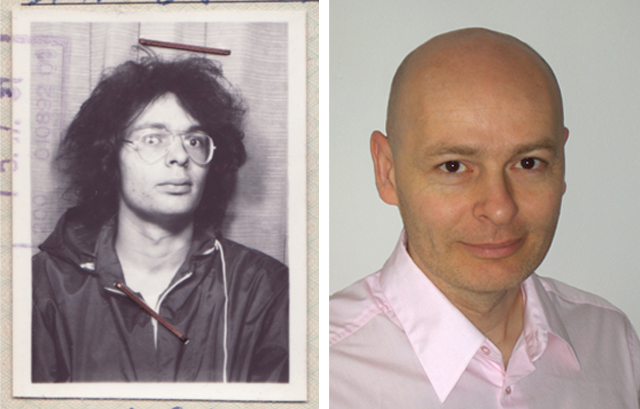

Fred Grimm has written an incredible illustrated book on the history of German youth that’s a major inspiration for us,“Wir Wollen Eine Andere Welt” (We Want Another World: Youth in Germany 1900 – 2010). Teenage Director Matt Wolf interviews Fred about his “collage of young thoughts and sounds” and our like-minded projects.

MATT WOLF: What inspired you to make a book about German youth through history?

FRED GRIMM: I tried to write a history book in a new way. My main question was: How was life for young Germans in 1901, 1923, 1938, 1957, 1972 and so on? What did they write in their diaries and letters? How did they love, think about politics, their parents, what were their hopes and dreams? The idea was to write a history book through a youthful and contemporary eye, a collage of young thoughts and sounds, which could give us a new view of history.

MATT: Wow, that’s amazing… In so many ways these are the same goals I have for the film Teenage. At first I was concerned there wouldn’t be material from the turn of the century, but I was wrong. Were you surprised by the depth of material you found from so far back?

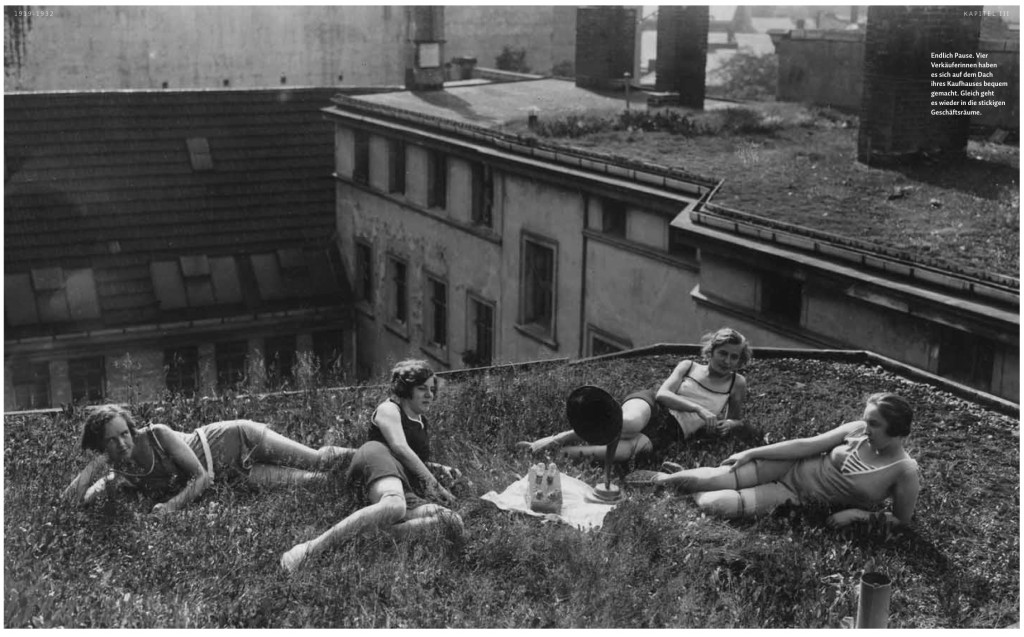

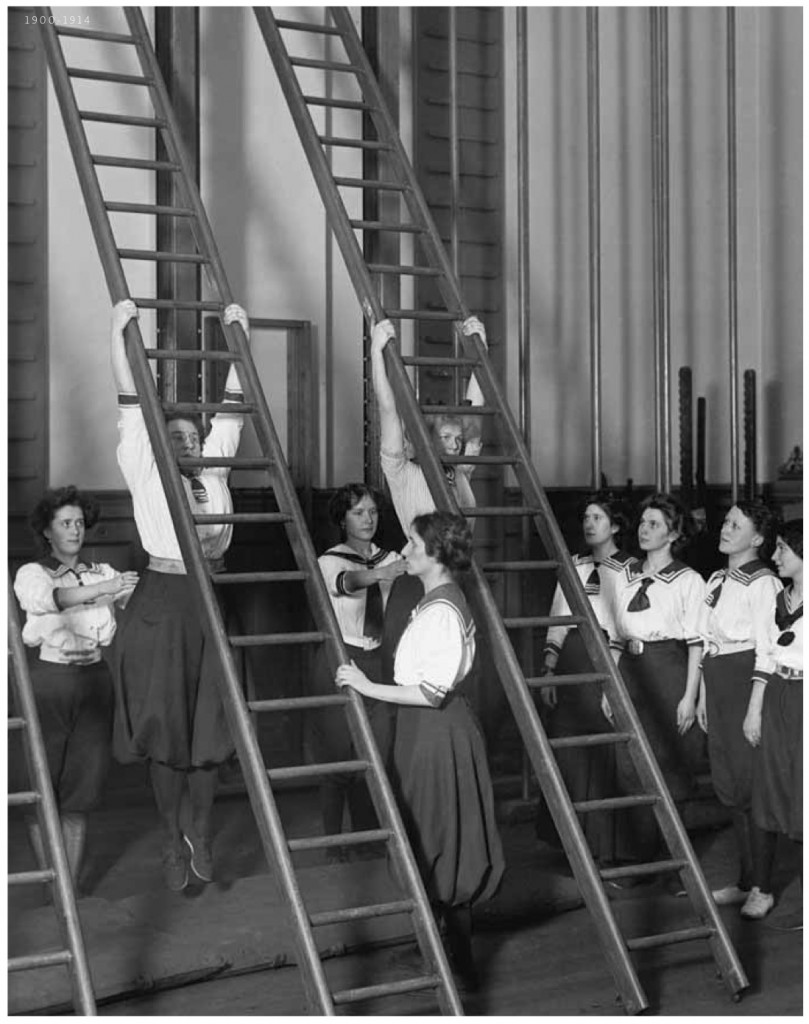

FRED: I was really thrilled about all the diaries I found in the archives. The texts were in a way really strange because many of them were written brilliantly, but within clear class structures and morals. It was near and far away at once. I read interesting material from young women, who were struggling with the society, which kept them in close borders. I found also material which was surprisingly close to youth feelings from today. It was very hard to come by texts from young workers—they just didn’t have the time to write a diary because they worked like 12, 14 hours a day from a young age on.

MATT: Something I’ve always found interesting about German youth culture is the impulse for youth to lead other youth— like in the Wandervogel. It’s different than most pre-WWII American or British youth movements like the Boy Scouts. Why do you think youth were always leading these movements in Germany?

FRED: After 1900 youth was sort of a big projection for different causes. Youth symbolized the New in culture and society, but the conservatives were also eager to get their hands on the young to stabilize their regime. Wer die Jugend hat, hat die Zukunft – Who got the youth, got the future, is a very common slogan from these days, leading to the rise of the Nazis as a really youthful party compared to the other political forces in Weimar Germany.

The Wandervogel is really, really interesting because there are so many ideas which found a place in this movement: Young left Utopians were Wandervogel, young women who wanted to break the rules as well, but also deeply nationalistic (“völkisch”) racists, anti-Semites and other guys reflecting on German blood. Wandervogel was a youth culture where you could find the soft-spoken longhaired dreamer AND the wannabe-soldier under one umbrella. For me the Wandervogel is a symbol of the dream to become free, to make your own decisions without parents or teachers, a very optimistic way of life.

But similar to Wandervogel emerged young worker organizations, where young Socialists tried to organize around their own interests and activities. The government thought: okay the Wandervogel is full of crazy bourgeois kids, but they won’t do us any harm because they aren’t that political. But young workers—that could be dangerous for the state—and the government banned all young workers groups in 1908.

MATT: I love the layout and design of the book. As a non-German speaker, I was wondering… is the book composed of many quotes from teenagers?

FRED: Yes… from diaries, letters, and essays. It’s a collage, trying to get the sound of the times. And thank you very much for the compliment—we tried hard to get it right, we wanted to include photographs with an authentic style and we used a very readable typography. The art director is Frances Uckermann she’s great! One of the best designers in Germany (but, to be honest, it was her first book, normally she works with magazines…)

MATT: What was one of the most exciting photographs or pieces of archival material you found while researching your book?

FRED: I was deeply moved by the letters young women and men wrote before they were executed by the Nazis. And the stories about the hate against Jews and the concentration camps were really chilling, but not in a voyeuristic way. Can you imagine the feelings of a young girl in a concentration camp who asked a guard for her parents and he just showed her the smoke in heaven: “There they are”!?

I really loved a diary from a young girl in Weimar Germany who changed her boyfriends, like, weekly or so, and the next one would always be her really big love! Very funny.

MATT: The legacy of the Hitler Youth must have been a heavy burden for young people after the war. How do you think that history affected or shaped post-war German youth culture?

FRED: Very much so—they had to get along with their parents who were drilled in Nazi Germany and didn’t changed very much after the war. And they had to come to terms with the shame. I mean, imagine you are fourteen-years-old, it’s 1952, and you know you live in a country where people let their own neighbors be killed, or even killed them by themselves. You got the feeling that the whole society is a masquerade and many young guys felt that anybody who did these crimes had no right to tell them what to do or, more importantly, what not to do.

It’s a tough upbringing in a country, which you couldn’t really love after all that had happened. There was a lot of public hate against the “Halbstarke,” young Rock’n Roll-Fans, who were described as animals. I read diaries where young girls and boys wrote: “Why do they hate us? We just want to dance and wear the clothes we like.” In that sense many young people after the war had to fight against Nazi Germany as well as against the Germany of the fifties. But I found also a sense of booming optimism of very liberal parents who were able to give their children way more freedom than today.

MATT: Today youth culture is very globalized— teenagers in New York probably obsess over the same stuff as their peers in Berlin. But how do you think youth are still different today in Germany than the rest of the world?

FRED: There is never ONE youth I guess. There are some things they share, but I see them as individuals so it’s pretty hard for me to answer this. But I would say German youth are way better, smarter, and nicer than their reputation. You could say this for the last hundred years as well. Young Germans are different for sure, but you might say this for young French, Italian, American teenagers as well.

All images provided by Fred Grimm, excerpts from Wollen Eine Andere Welt

—Fred Grimm is a journalist, historian, and author who lives in Hamburg.

► Buy the book Wir Wollen Eine Andere Welt by Fred Grimm